CIVIL DISCOURSE

“We have seen our discourse degraded by casual cruelty. At times, it can seem like the forces pulling us apart are stronger than the forces binding us together. Argument turns too easily into animosity. Disagreement escalates into dehumanization. Too often, we judge other groups by their worst examples while judging ourselves by our best intentions—”

Definition

If you found this page, you know the most popular political position in the U.S. today is “I’m right, and you’re evil.” As an antidote, my working definition of civil discourse is respectful, truth-seeking conversation about areas of shared concern about which reasonable people are apt to disagree.

vision

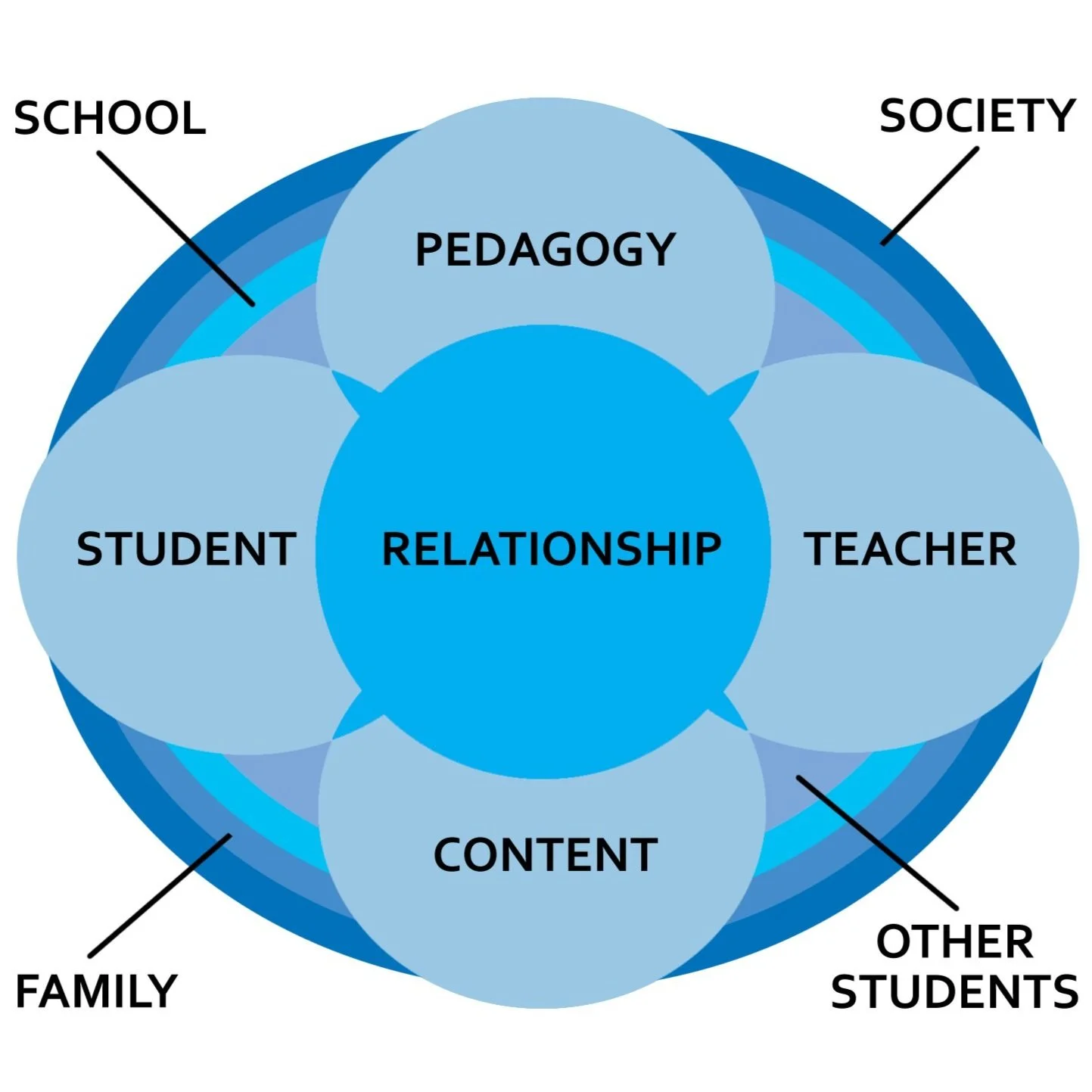

A world where schools provide possibilities for students to engage in respectful, reason-based discussion. Moving beyond debates with “winners” and “losers,” students learn that they are capable of participating in meaningful conversations in which they help each other think through matters of genuine, mutual interest.

In my dream schools, the topics students discuss aren’t necessarily the most charged, hot-button issues—at least, not right away. (You can’t engage such subjects productively before respect and trust have been established over time.) However, teachers can identify opportunities for lower-stakes civil discourse in every classroom: How much homework is reasonable? What makes this approach to solving this proof more reliable than that one? Could we try class outside today? Why should students (and the rest of us) deliberately spend time apart from our phones?

Caption by high school artist Camila Hernandez for her silkscreen in a public school district’s art show (2015): “Technology is a growing phenomenon that has no stop to it. Over the years, people of different ages have gotten way too attached to their devices. We are losing our communication and socializing skills because of how much time we spend on our iPads and phones. We are imprisoned in our own lives, with the ability to be free.”

14-minute VIDEO FOR HIGH SCHOOL TEACHERS

Click to watch this short video produced by Action J Productions. Designed for high school teachers, the video presents four strategies for helping students engage in respectful conversations.

citizens (not just consumers)

As a classroom teacher for 18 years, I focused on designing some school experiences such that students could see themselves as citizens possessed of the power to engage the larger world—and change it. Their role as citizen, of course, is only one of the ways I would like for students to see themselves, but it is a public identity that should be available to everyone.

It’s unfortunate the “politics” is often a dirty word these days. The Greeks who gave us the root didn’t regard it that way. Thoughtful educators can help reclaim it. (Slide from CD deck)

Not all citizens run for office, or engage frequently in political discussions; but neither can a citizen view themself as only a consumer. A citizen possessed of the power to change the world knows how to read advertising, understands how to spot fallacies and how to construct a strong argument. They know how to ask questions, how to demonstrate respect for other parties in a conversation, how to collaborate. A citizen understands the value of history, including its misuse as propaganda. They appreciate research as a way to understand a situation or culture or problem more fully. The citizen recognizes that everyone’s perspective will be slightly different, so they need to get better at listening. When the time comes for action, action can take many forms.

Beginning with the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, I co-moderated a series of after-school discussions open to all members of the high school community. We were explicit about ground rules, especially that the point was not to debate. Participants were welcome to challenge each other, but the point was to explore thoughts, questions, and concerns together.

Like critical thinking, civil discourse is a skill students need practice to develop. Very few kids learn how to change their minds at the dinner table, and actual hard conversations yield such poor video content that they’re unlikely to appear on YouTube or TikTok.

If schools don’t provide opportunities how to have reasonable, non-threatening, respectful conversations about topics that are difficult to talk about, how can we expect students to become thoughtful, engaged citizens?

In 2015, my last year leading Project ‘79 in New Jersey, a student commandeered the board in our common room to share thumbnail biographies throughout Black History Month.

related podcast episodes